Theodosius, St Ambrose, and the "Excommunication" of Chris Coughlan MP

Why the Church sometimes has to cut people off, even politicians.

Whenever a vote in Parliament touches on a ‘moral issue’ on which the Catholic Church has pronounced a definitive moral teaching, the same news story inevitably crops up a few days after the vote: a Catholic MP has voted against that definitive moral teaching and is now shocked and appalled to discover that there are consequences for their actions. This Sunday’s unhappy camper is Chris Coughlan, Liberal Democratic MP for Dorking and Horley, who voted in favour of assisted suicide despite a written warning from his Parish Priest that there would be consequences. Writing in the Observer (‘Priest denies MP Holy Communion’ 29 June 2025) Coughlan called the priest’s behaviour ‘outrageous’ and he followed this up with a triad of tweets, criticising the decision further. In a particularly telling comment he said ‘My private religion will continue to have zero direct relevance to my work as an MP.’ This compartmentalisation of religion from public life is precisely the problem with regard to Coughlan’s vote - and the reason why “excommunication” in this public and dramatic manner was necessary.

This incident raises two important questions: (1) why does the Church ‘excommunicate’ people? and (2) can politicians legitimately separate their faith from their public office? The answers, in brief, are (1) because we love them, and (2) no, they cannot.

Why do we Excommunicate?

Cardinal Josef Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, was once doorstepped by a journalist after Mass. He asked the Cardinal about his sermon; if God is love, how do you reconcile that with the inquisition? Unfazed, Ratzinger answered that love and truth always go hand in hand. When another is in error, especially a grave error of faith or morals, anyone who loves them has an obligation to bring them back to truth. When they lead others into that same error by teaching or by example, the Church has a responsibility to publicly rebuke them - to correct the error. This responsibility is rooted in the teaching of Christ himself. The Lord tells a short parable, that of the lost sheep, that the Church should be like a shepherd with one hundred sheep, leaving the 99 to go after the lost one. In that context, he then instructs;

If your brother sins, go and point out the fault when the two of you are alone. If the member listens to you, you have regained that one. But if you are not listened to, take one or two others along with you, so that every word may be confirmed by the evidence of two or three witnesses. If the member refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if the offender refuses to listen even to the church, let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector. (Matthew 18:15-17)

The one who sins is a ‘lost sheep’ and a well-timed rebuke, if he listens, brings him back into the fold. But, if he does not listen, he has to be treated like a ‘gentile or a tax collector’ - cast out, cut off, interacted with as little as possible (if at all). This is the meaning of ‘excommunication’ - cut off from the communion (fellowship) of other believers. Cut off in this way from other believers, they are also cut off from the Eucharist, which is the symbol and cause of unity among Christians.

Whenever, in the history of the Church, someone has publicly done something gravely evil, or has taught some serious moral or doctrinal error - the Church has responded in the same way. Their brothers and sisters have called them to repentance, their pastor (the Bishop) has called them to repentance, and the Church as a whole has called them to repentance. If they would not listen to their brothers and sisters, to their pastor, and to the Church, then the Church as a whole has pronounced the same sentence ‘let them be anathema’ - in other words ‘let them have nothing more to do with us.’ The word often used for this in the ancient Church was ‘disfellowship.’

However, even this grave ‘punishment’ is not an abandonment or a permanent expulsion, it is always ordered towards the return of the ‘lost sheep.’ When we sin, through doing evil and teaching others to do the same, we put our souls in grave peril. The Catechism describes sin thus;

Mortal sin destroys charity in the heart of man by a grave violation of God's law; it turns man away from God, who is his ultimate end and his beatitude, by preferring an inferior good to him. (CCC §1855)

The soul, in a state of mortal sin, is dead - on a one way road to perdition. By abusing our freedom and choosing to do something evil, we risk eternal punishment. The Church uses the ‘punishment’ of excommunication as a means of calling a sinner’s mind back to this grave reality - to help them come to their senses and repent before it is too late. But the Church, even when cutting someone off in this drastic manner, never fully abandons them - the hope is always that they will come back.

Perhaps the best illustration of this comes from the Rule of St Benedict - the rule which governs the ‘perfect’ Christian society (the monastery). Seven chapters (ch.23-29) are dedicated to the subject of ‘excommunication’ following the same rule given by Christ in Matthew 18. Those who refuse to follow the Rule, or who disrupt the harmony of the community, or who commit some grave fault, are to be rebuked. If they will not listen to the rebuke, then they are to be ‘excommunicated’ - which in the context of the monastery means that they are to eat their meals separately from the community, that they are not to lead any of the prayers in the chapel. In the case of grave fault, St Benedict says “Let not any of the brethren consort with him nor talk to him.” and commands that nobody should either bless him or his food. Yet, in all of this, Benedict adds:

With all solicitude let the abbot be careful for offending brethren, because: “It is not the healthy that need a physician, but those that are ill.” And so he ought to use every means in his power like a wise physician and send colleagues, that is to say wise senior brethren, to console as it were hiddenly the wavering brother and incite him to make humble satisfaction; and console him that he be not swallowed up by over-much sorrow, but as the Apostle says: “Let love be strengthened in him”; and let prayer be offered for him by all.

For the abbot ought to be solicitous with much diligence and to take care, with all sagacity and industry, that not one be lost from among the number of the sheep entrusted to him; for he must know that he has undertaken a cure of weak souls, not a tyranny over strong ones. (Ch.27)

The ‘lost one’ is never abandoned, but repeatedly counselled to repent and offer penance and satisfaction for his sin, and (above all) he is to be prayed for.

Why do we excommunicate? Because of love! Because we can see one of our own playing with fire and we want to snatch them from it before it’s too late and that fire consumes them. We can never be content to leave someone to their own devices, separate from the love of God and the salvation of His Christ. If we were, we would not truly love them.

Why do we excommunicate publicly? The Sin of Scandal

Excommunication is sometimes, regrettably, necessary. But there is a secondary question, one which Coughlan also highlights in his own response: does it need to be public? Did his parish priest need to announce to everyone what he had done and what the consequences were going to be? Did he need to announce it to his neighbours and his children’s school friends? Was this also an act of love?

When we sin, our sin is for the most part ‘private’ - something we think, or do, or fail to do in our private lives. It is, so to speak, between us and God. When we bring these sins to our Confessor he absolves them privately, sets us a private penance, and sends us on our way shriven from the sin. Nobody else, except perhaps those with whom we have sinned, is ever any the wiser. In fact, it is a grave secret, preserved by the threat of excommunication reserved to the Apostolic See (Canon 1388 §1) - a priest who violates it can only be readmitted by the intervention of the Pope or his Major Penitentiary.

But sometimes our sin is not our own. A ‘notorious’ sinner is one whose sins are known by his neighbours and friends already - the classic example (used by St Paul and by St Augustine) would be a notorious adulterer or bigamist who cheats on his wife or marries another while his first wife is still alive, whose adultery is known to everyone. When the sin is public and well known, the sinner does not have the same right to privacy he had when the sin was ‘occult.’ This is because the notoriety of the sin means there is the danger of a second, more serious, sin; the sin of scandal.

By scandal it is not meant ‘shock’ - one can be scandalised without being shocked and appalled at all - in fact, the essence of the sin of scandal is that the ‘scandalised’ party is not shocked but misled. A scandaliser is one who not only does evil but does it in such a way that others are led into doing the same; he makes his sin look attractive, socially acceptable or even prestigious, or (at the very least) permissible. The first sin damned only the sinner, but the ensuing scandal risks damnation for others. The Catechism offers this on the sin of Scandal:

Scandal is an attitude or behaviour which leads another to do evil. The person who gives scandal becomes his neighbor's tempter. He damages virtue and integrity; he may even draw his brother into spiritual death. Scandal is a grave offence if by deed or omission another is deliberately led into a grave offence. (CCC §2284)

Of scandalisers, Jesus says this:

If any of you put a stumbling block before one of these little ones who believe in me, it would be better for you if a great millstone were fastened around your neck and you were drowned in the depth of the sea. Woe to the world because of stumbling blocks! Occasions for stumbling are bound to come, but woe to the one by whom the stumbling block comes! (Matthew 18:6-7)

When a grave sin is ‘public’ or ‘notorious’ the Church has an obligation not only to impose the penalty of excommunication, but to do so publicly - to avoid the risk of scandal. Chris Coughlan’s sin is not private to him - it was committed in public, in virtue of an office he holds. The members of the parish community know that their MP is a Catholic, and (presumably) that he voted in favour of Assisted Suicide, this is the very definition of a notorious sin. In this circumstance, the parish priest was under an obligation to issue a correction. Chris’ evil act risked the corruption of his friends, his neighbours, and his children, unless the Church took a stand. The public ‘excommunication’ was a lesson, born from the love of a father for his spiritual children, to keep them safe from one would lead them to sin. Losing one soul to sin is a tragedy, losing an entire community to it would be catastrophic, so the parish needed to be in no doubt that their MP had done wrong and could no longer be one of them.

When the Fathers of the Church wrote about the sin of scandal, they compared it to a rotting limb - it needs to be cut off for the good of the whole body. The priest (and, ironically, eventually condemned heretic) Origen of Alexandria wrote this in powerful terms:

If I, who seem to be your right hand and am called presbyter and seem to preach the word of God, if I do something against the discipline of the Church and the rule of the Gospel so that I become a scandal to you, the Church, then may the whole Church, in unanimous resolve, cut me, its right hand, off, and throw me away.1

Thus, for the good of their own soul, an obstinate sinner needs to be excommunicated. For the good of the entire community, the notorious sinner must be publicly excommunicated. One final question now remains: is there any difference when the sinner is a politician, and the ‘sin’ is some official act or duty he has to carry out. Does the obligation to ‘represent’ a constituency or to follow orders from a ruler cancel out the individual moral obligation?

Compartmentalising

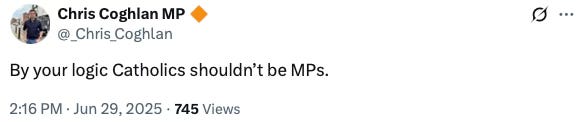

Coughlan’s defence of his position on X (the-website-formerly-known-as-Twitter) was that his duty as an MP was to his constituents, the majority of whom are non-Catholics and who (presumably) don’t share the view of the Church. His original comment ‘My private religion will continue to have zero direct relevance to my work as an MP’ was followed-up by two direct replies to me. The first;

and the second;

If I were a more flippant character, I might have penned a more acerbic reply (‘By your logic MPs shouldn’t be Catholic.’) Coughlan’s point is wrong, but too important for a flippant response. Too many Catholic politicians (and not just in Britain) think of their faith as something ‘private’ or ‘personal’ - something which they have neither the right nor the responsibility to bring into their work as public officials. Some feel their own opinion matters less than the majority opinion.2

The late great Labour MP Tony Benn, in ‘Letters to my Grandchildren’ gives short shrift to this kind of argument;

I have divided politicians into two categories: the Signposts and the Weathercocks. The Signpost says: 'This is the way we should go.' And you don't have to follow them but if you come back in ten years time the Signpost is still there. The Weathercock hasn’t got an opinion until they've looked at the polls, talked to the focus groups, discussed it with the spin doctors. And I've no time for Weathercocks, I'm a Signpost man.

When we vote for an MP, we aren’t voting for a yes man who will sway with the wind. We are voting for someone whose values reflect our own and who we trust to vote in accordance with those values. We vote based on values and trust; does this particular candidate share my values when it comes (for instance) to the sanctity of life, care for the poor, immigration, the NHS, international affairs etc, and do I trust them to uphold those values when they vote? They aren’t the delegate of the majority, but an individual with a definite system of values with a right and a duty to do what is right by us. Sometimes that will accord with what the majority wants. Other times, that will fly in the face of the majority. A good MP is a signpost - who votes based on what is right or wrong. Sometimes they will be punished for that at the ballot box, but they will have done what they believed to be right.

If this is true of political values it is doubly true for the Catholic Faith. Being a Catholic isn’t a badge you wear on a Sunday and when looking for a school for your children which you can then take off when it no longer suits you. Being a Catholic means committing to follow Jesus Christ along the hard and narrow road - allowing Him to take you and shape your life until you become an image of Him. The image of Christ is one which is, above all, humble and obedient to God the Father, the same God who inscribed a moral law in the hearts of every human being (the moral law which all people hold; do not murder, do not steal, do not commit adultery, do not lie, honour your mother and father). That image of Christ is also a sign of contradiction, which will be rejected by the world;

If the world hates you, know that it hated me before it hated you. If you belonged to the world, the world would love you as its own. Because you do not belong to the world, but I have chosen you out of the world—therefore the world hates you. (John 15: 18-19)

Christ taught what was true and did what was good, and as a reward he wasn’t elected to any public office. He was arrested, beaten, tortured, crowned with thorns, and crucified.

Two standout saints in our own English tradition, St Thomas Becket and St Thomas More, demonstrate the authentically Christian way to exercise public office. Both held the office of Lord Chancellor, in their time akin to Prime Minister, and were asked by the King who appointed them to violate their religious conscience - Becket to strip the Church of its legal protections and privileges, More to recognise the King’s adulterous marriage and headship over the Church. Both refused. Both were Martyred for it. On the scaffold before he was beheaded, St Thomas More set out a charter for politicians who profess the Catholic Faith: ‘I die the King's good servant, and God's first.’ Dividing the faith from public office, as Coughlan seeks to do, belies either a lack of faith or a lack of moral courage. The Christian faith is lived out in works, without which it is dead.3 If it can be put on and off at will, or when it becomes inconvenient, it is no faith at all. Even Ridley Scott, writing the script for the film ‘Kingdom of Heaven’ understood this basic point: ‘When you stand before God, you cannot say, 'but I was told by others to do thus,' or that 'virtue was not convenient at the time.' This will not suffice. Remember that.’

Theodosius and St Ambrose

This article has already been a long read, but something must be said to bring all these various arguments together, and relate them back to the courageous decision made by Fr Ian Vane to publicly announce Coughlan’s exclusion from the Eucharist. The ‘something’ is the clash between the emperor Theodosius and the Bishop of Milan, St Ambrose.

The emperor, angered by the death of his governor in Thessalonica, lost his temper and sent orders for the population to be massacred. He would later relent and send a counter-order, but the order arrived to late and several thousand were already dead. The Bishop St Ambrose wrote to the Emperor - refusing to even celebrate Mass if there was a chance the Emperor would attend to receive Communion;

‘I dare not offer the sacrifice if you intend to be present. Is that which is not allowed after shedding the blood of one innocent person, allowed after shedding the blood of many?’ (Ambrose, to Theodosius, para. 13)4

Instead, the emperor was required to do some public penance, like David after the murder of Uriah, and to publicly repent of his sin. The master painter, Peter Paul Rubens, reimagined this letter in a painting (above) of Ambrose barring the emperor entry into the Church at all. Did Theodosius complain about Ambrose? Did he accuse him of a humiliation? Did he whine that his friends and his children’s friends had heard him being criticised? No. Theodosius went like a penitent to Church, dressed in common clothes rather than Imperial robes, and abstained from Holy Communion until Christmas, when Ambrose publicly forgave his sin.

Humility, rather than any attempt to drag the good name of a priest through the mud for doing his duty. A mea culpa, an apology, a recognition that what you have done was morally evil. Theodosius saw the risk to his soul, I wonder if Chris Coughlan MP sees the same risk?

Origen of Alexandria, quoted in Hans Urs Von Balthasar ‘Spirit and Fire’ p.5

I am responding to his argument as made, that personal conviction comes second to his duties as a representative but I feel I should add, for the sake of clarity, my own doubt that Chris Coughlan is personally opposed to Assisted Suicide. My suspicion is that this argument of duty over conscience is being made in bad faith and that he simply disagrees with the Church’s teaching and is more than happy to go along with the majority on this issue. This assumption may be wrong, in which case I apologise for making it.

Cf. James 2:14-19, in particular ‘someone will say, “You have faith and I have works.” Show me your faith apart from your works, and I by my works will show you my faith. You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe—and shudder.’

Trans. H. de Romestin, E. de Romestin and H.T.F. Duckworth. From ‘Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers,’ Second Series, Vol. 10. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1896.)

Good post. You might also add the public penance of the King after the murder of St Thomas Becket, which I think involved being flogged by monks. Though I suspect it could have been a little symbolic?